The Victorian era instantly summons images of stifled womanhood and over-buttoned men. In a world of rapid transformation men and women gripped tightly to certain signifiers in order to navigate the changes in their mental and physical landscapes.

During the Victorian era the leading shapers of metaphysical thought were implementing a scientific reductionism centered around the stories of Darwinism, electro-magnetics, and atomism.

The era of the World Wars would cement these narratives deep into our cultural psyche. Despite a brief moment in the 1950s where the Victorian archetypes of gender threatened to make themselves eternal, the dissolution was to continue. One baby boomer once wrote that when the mothers dropped their children off at college in 1968 they all wore gloves. By 1972 they had vanished utterly.

What makes gloves intrinsically feminine? Why bother with arbitrary totems that are meaningless elsewhere? Fifty years of “What does it matter?” would follow. Why should a woman be pregnant? Why should a child be given care in the home? Why should anyone breastfeed? Why shouldn’t household chores be split 50/50? Why shouldn’t the sexual marketplace be “equal”? Why should men restrain their sexual appetites? Why shouldn’t women have dreams, eat peaches whenever they damn well please, and achieve “greatness”?

There were, it seemed, no good answers to these questions in a culture where secular advertising images had replaced transcendent archetypes. The criticism of most traditionalists was ignored: the world had clearly changed. Women went to the office. Electricity was in the home. Fertility could be managed. Children could be dropped off at daycare.

For a little while people tried to have the best of both worlds, all the while using up the topsoil beneath their feet. We have been slow to realize the implications of the revolution of “But why does it matter?”

With the loss of meaning, purpose, and a sense of vertical orientation, disoriented people have flocked to the idea that while they are only a clump of cells they also have an inherent “self” which is male or female. The body is wrong but the customer is always right.

Archetypes of masculinity and femininity signify difference. In a world composed of interchangeable atoms, where some people are reduced to clumps of cells, difference insults. Difference offends the machine and the algorithm, signifying an archaic complementary factor in Creation. The Machine prefers its lonely standardization.

The dead are equally dead. A living world, however, must necessarily overflow with differences and forms. Upon each flower is an archetype of form, invisible in the seed but revealing itself particularly in fruit and blossom. These differences are what make a living garden.

The differences of masculinity and femininity are deemed offensive in a flattened world transforming into a giant machine. The meaning of the body is denied and, despite the embrace of caricatures of the archetypes, a unisex androgyny becomes the norm (as does sterility.)

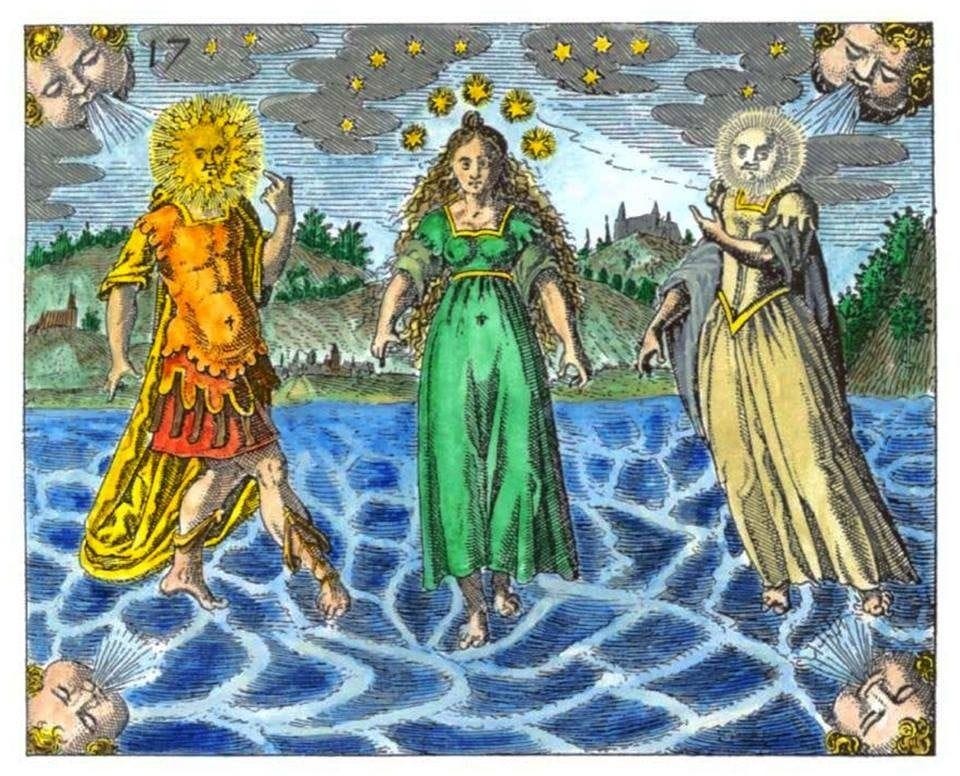

The archetypes may seem to be hiding, but just as light pollution seemingly masks the stars, the heavens remain all the same. For those who wish to ask what it means to be human in a world dominated by machines it may be time to rediscover the archetypes which lead us into greater communion with our bodies and communities. What I’d like to focus on are several questions:

-How did we lose the archetypes?

-What are the lessons we can take from the age of radical atomism?

-Should we rediscover the masculine and feminine?

-What would the masculine and feminine look like in a society seeking to impose a post-body dystopia?

I will try to briefly answer these questions in my own way, with hopes of seeding some faith that the transcendent is real and it is a gift.

1. How did we lose the archetypes?

Ivan Illich’s Gender points out that vernacular (read: non-professional) roles of gender were undermined by technocratic values over the past few centuries. Institutions have not stopped colonizing the peasants: indeed, they do so more than ever. At the heart of these transformations are issues of the family: what does it mean to have a home, to labor, to marry, to be a family?

Contrary to narratives centering the female, it is men who suffered the first wave of archetypal loss, and men who inflicted it.

If femininity is in dramatic crisis right now (“what is a woman?”), masculinity began its crisis several hundred years ago. Working class men were dragged from the land during the era of enclosure into the factories and mines for the ruling class. Millions of men were severed from the fruits of their labor, replaced by machines. What was left was their body reduced into a mere automaton, hacking coal or pulling levers so some men could be millionaires and remake the world in their image.

These changes in the lives of the people were the manifestation of mental changes in the minds of these men of power. As the state grew a class of men was empowered to seek greater control of society and nature. The cloistered schools of logic birthed the nominalists who birthed an era of occult science, where monarchs rewarded men who increased the strength of the state. The will of these leaders was divorced from the needs of their communities, and in their conquests of nature they imposed their narrow understanding of reality upon the powerless.

Medieval Christendom archetypes of masculinity had brought about the ideal of gentlemen and chivalry. Like the yin/yang, there was a seed of the feminine within the masculine, and notions of complementarity hallowed the warrior ethos and created an abundance of romance literature. But as the fertile ground for these archetypes was literally enclosed by the ruling class, a caricature of the masculine archetype would awaken in advertising and media in the guise of the rugged cowboy. This was the pitiful offering given to millions of office drones and miners: you who suffer and die to build the skyscraper lofts, take comfort! Someone, somewhere, rides free under the sky. Buy his cigarettes!

This was what was left after the revolution came for men: a technocratic class which used only the mind, a working class of millions cut off from the fruits of their labor, and a shrinking class of individualists used as fodder for advertisers.

During the industrial era a class of women, no longer running estates in the countryside, were heaped with their own signifiers and stereotypes. As the productive home was lost, women were made its raison d’etre. It was, media suggested, for her happiness and safety that all this had happened. A (temporary) cult of sentimental motherhood emerged even as the technological revolution undermined her as much as it had the male. The loom was moved to the factory, the servants replaced by dishwashers, the meals replaced by microwaves, and after another century upper-middle class woman in particular would feel as pointless in the home as her husband.

If class consciousness was the masculine response to the industrial revolution, feminism was the feminine response to the consumer product revolution.

Rather than re-engage with what they had lost and transform it, thought currents emerged from both groups which responded to the abuse of power by grabbing it for themselves. Men were disassociated from their limbs, women from their wombs, and the main response was to demand more disassociation.

The result are unisex roles, a mass mental health crisis, age segregation, removing vulnerable infants and toddlers from family care, a loss of understanding of cause-and-effect, widespread pharmaceutical pollution, pornified culture, and many hurting men, women, and children. The ring of power corrupts all who seek to wield it.

2. What are the lessons this radical atomistic view of the body can teach us?

We should try to draw good from the bad rather than merely react to these developments by picking and choosing past signifiers we like and clutching them. Many traditionalists go as far as wanting to veil women while heavily using technology that can provide an instant gateway for their children to a dystopia of porn.

We no longer live in the world of our ancestors. But the good news is this world we have is not merely a succession of nightmares unfolding on glowing screens; there is a vertical dimension to our lives. We once walked in the transcendent as in a dream; now we are invited to put down our adolescent rebellion and hallow that which has been given us: “For now we see through a glass, darkly; but then face to face: now I know in part; but then shall I know even as also I am known.”

We have lost much but have also been given the gift to encounter the the world in a free way. Each of us has an opportunity to choose our humanity, to choose to tune our bodies closer to Creation rather than the Machine.

This does not mean these days aren’t perilous, and that people aren’t sacrificed to the Machine. For many the encounter with gender ideology will scar their bodies for life. It does tear apart families, it does breed psychic disorder. Vulnerable children are deliberately confused and abused. Our best efforts to find a way through these tragedies must center the Cross. What we are to do is not choose the loveless path of denying suffering and destroying our bodies, but pass through it into a renewed life.

3. Should we rediscover the masculine and feminine?

To rediscover our respective masculinity or femininity means to embrace our givenness. Given, not accidental. Who is the gift-giver? From whom comes the clay and from whom the life-giving breath?

The hands which accept what they are given can encounter in communion with matter, and help hallow it, leaving something beautiful for generations to come.

Hallowed masculinity and femininity are signposts. Children particularly take comfort in stability and routine, which is why efforts to disconnect them from their bodies are particularly upsetting.

We can find the transcendent in cycles, complementary forms which ebb and flow at their proper time. Through the repetition of day and night, the lunar month, the solar year, we experience the transformation of time and space and certain eternal truths emerge. It is no coincidence that the rise of the unisex machine takes place in a society that lives indoors, avoids temperature changes, and insulates itself as much as possible from the flesh. Rather than engage the complementary cycle, the Machine chooses flat standardization.

Willingly yoking ourselves to these cycles heals our bodies. Our entire endocrine system can rest when it enters these rhythms. Our bodies become physically disordered and ailments abound when we are forced out of them. There is truth and healing in leaving the Machine for Reality.

The same applies to masculinity and femininity. Rejecting the archetypes in favor a pre-packaged unisex identity leads to disassociation from the body. We lose understanding of ourselves, our homes, and our communities. It is not enough to stick to chromosomal definitions of male and female. XX and XY may have the merit of genetic truth, but they cannot tell us how to live, and we see the consequences of that failure of vision all around us. It is not to the smallest we need to look, but to the eternal. Our healing requires we rediscover the transcendent.

4. What would masculinity and femininity look like in a society seeking to impose a post-body dystopias?

In the Machine we are offered (at least for now) a choice between the unisex denial of the body, and advertising-based caricatures. Exaggeration of the gender binary or the rejection of it, but never a loving, complementary fulfillment of it.

If we choose to embrace the masculine or the feminine in a flattened world, devoid of the heavens, it will too often becomes a performance for others. It takes openness to the idea we are Created to transform our perspective and re-arrange our values. It is when we stop performing vocal fry, competitive mommy-blogging, or engaging in Kardashian-plastic surgeries for Instagram that we see our givenness as something to harmonize with the transcendent rather than a mere tool to gain status.

There are local stories of masculinity and femininity around the world which manifest aspects of the universal archetypes best suited to that particular time and place (and it’s important to remember what I’m calling the archetypes are not mere metaphors). Masculinity in the Arctic and masculinity in the Outback will vary in appearance; hallowed masculinity in a modern city will have different tasks than hallowed masculinity on the farm. The signifiers are not meaningless, but neither are they ultimate. They are textural signs of our particularity, and it is up to us to re-engage Creation by figuring out how we can best redeem the appearances.

Women have a particularly difficult path considering the temptations currently pushed on them. The pagan renaissance of the 20th century rediscovered archetypes of feminine, only, like previous unbalanced societies, turned these archetypes into perfected idols. All women are goddesses deserving worship; the ability to give life becomes a power the woman commands rather than a gift she channels.

Not only that, but this renewed matriarchy sees itself as fundamentally at war against masculinity. Instead of embracing a complementary understanding of masculine and feminine, this caricature sees the female as complete in and of itself, while also ironically prepared to swallow any pill from male-dominated industrial medicine to repress the female body!

These are confusing temptations indeed, and it is imperative that we work past them. The crisis of masculinity manifested in the bitter class-manager wars of the 20th century and have never been resolved. The price for this failure has been a centralization of power, loss of environmental stewardship, and mass social alienation. If we do not find a way to rescue the feminine archetype from its inverted caricature the home and family will completely dissolve and the institutional machine will become the sole manager of earthly affairs.

Embracing our respective masculinity and femininity through the archetypes is the best way to restore a complementary existence which gives life to one another rather than sowing alienation so we are rendered dependent upon the machine.

Coming to understand these archetypes after a lifetime of immersion in the “You can be anything you wanna be!” culture can be painful. It takes years of opening ourselves up to our strengths and limits, understanding how we interact with others, accepting our shortcomings, and taking responsibility for our choices. This is not a path we can walk for one another; that is the very opposite of taking responsibility. However we can point one another in certain directions we have found enriching, and I will point towards one now in order to help those readers who would appreciate a hint for their own journey.

In a Machine society, speed and strength are the highest priorities. As unfortunate and unfair as it may seem, women are neither as fast nor as strong as men. No early childhood conditioning can or should change our bone structure.

Women, though, are far more flexible. This creates a capacity for great beauty and grace, but these qualities have been scorned by those feminists who only value the quantitative accomplishments of men and would impose unisex (ie machine) standards on the female body.

This preference for masculine strength, speed, and power is rife in sports, arts, technology, and medicine. Without a feminine balance these virtues become suffocating for both men and women, who lose a vital qualitative part of the human experience.

We can find a tragic reflection of this confusion in the meme which appeared after the Dobbs decision, where a pregnant woman presents herself as in competition with her child, and argues with an invisible deity: “What of my greatness?”

Confusion abounds. Why does only the greatness of the warrior count? Why is the female body, ill-equipped to wear heavy armor, to be denied its own strengths, as in the stamina of child-bearing? Why is the female gift of nurturing seen as lesser? Why is greatness only in accumulating power, and not in giving life and beauty?

The elites despise the female body. Masculinity and femininity among the rich are reduced to mere signifiers and surrogacy is normalized. The wealthy dream of artificial wombs. The face is lifted, the breasts are hacked off, the body tweaked, and the life-giving connection between men and women reduced to a mere performance of permanent sexual availability.

Those who would live in a human world are called to re-evaluate the significance of these interventions in our bodies. Do we treat our fertility as a gift to be known, or do we accept interventions which we little understand?

Do we encounter a world which thought of these issues long before Judith Butler, and re-approach ideas like yin/yang and complementarity? Do we allow ourselves to see the flexible strength within femininity and the gentle stewardship within masculinity?

Do we know ourselves more, or less? Do we accept our particular strength as a gift to return to our communities?

What has happened need not be a curse. We have passed through centuries which upturned much of what we thought we knew, and now we have a chance to recover eternal truths in a new way. Those who want us to stay in an adolescent rebellion forever, angry at our bodies and our parents and society, are denying themselves the gift of encounter and growth.

Our manifestations of these archetypes will come with a conscious choice to be responsible to others. If we display chaos to children, this chaos will follow us. If we encourage the degeneration of choice into the Frankenstein assemblage of discordant parts, we will accelerate the breakdown of our bodies. If we tell ourselves ourselves matter is meaningless, we will replace what is lovable with what is loveless.

We are entering an era where we increasingly have to choose to be human or a machine. The archetypes can guide us in this choice, softening the pain and offering us an understanding and redemption of our sufferings.

Your body is not mere atoms. Your body is not a collection of parts. You are not Frankenstein’s monster. You were made eons ago by the Most High Holy Trinity, and you have received the gift of re-encountering your body to transform this matter into a reflection of the Holy Archetypes, and give it back with love.

It’s not a journey to miss.

THIRD SIDE COMMENT (can you tell I am reading this while trying to help Kriti craft)... there were some remarks at the last ACCS meeting about how technology has disconnected us from natural rhythms. An agrarian society obviously respects the authority of the seasons. Now, most of us have jobs where we don't care at all what the weather is. Louis Markos, sort of accidentally found himself saying, and then seemed to regret saying, that women still find themselves subject to a monthly cycle for half of their life and that's one of the last examples left where we are forced to respect the natural rhythm. I found the comment interesting.

SECOND SIDE COMMENT... Douglas Wilson has a nice comment where he says, "medieval societies taught their children to find their proper station in life. Modern societies tell children they can be whatever they want to be. It should be obvious which society is lying." Goes for sex, goes for many things. All of us have some givenness to be respected.